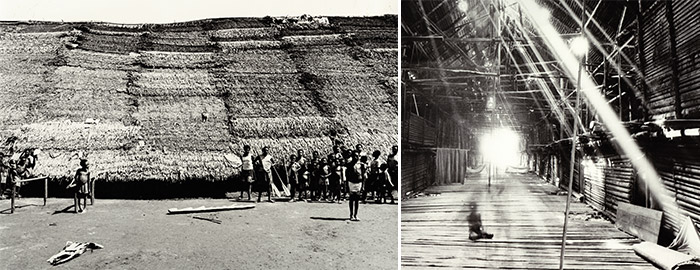

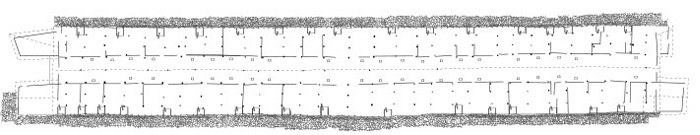

The Gogodala longhouses situated on the Aramia River in the Western Province of Papua New Guinea rank among the country’s largest traditional constructions and the largest structures made of vegetable material in the world. They reach a length of up to a hundred and fifty metres, a width of twenty-five and a height of twenty metres.1 In terms of expansion and volume, the four-storey buildings are literally outstanding in the context of traditional Oceanic architecture. Erected on elevations in the wet and swampy lowlands north of the Fly River, the oblong communal houses genamo conflate the concepts of settlement and dwelling in so far as the longhouse provides housing and living space for an entire village population while at the same time the whole village fits into one single building. In other words, village and building become one, a single architectural structure. Gogodala society and culture are pervaded by multiple sets of binary oppositions, which also find expression in the architecture of the local longhouses. It is here that the inherent social, religious and mythological dualities become lived space. The architecture of the genamo represents an interface of the fundamental polarities that shape Gogodala life. By encapsulating these polarities in an ordered structure and offsetting them against one another, a coherent whole emerges. The spatial articulation of fundamental oppositions and their integration in the genamo, in both tangible as well as symbolic terms, by means of an architecture that encompasses the collective totality engenders social and cultural cohesion.

Total Architecture - Opposition and Integration in the Gogodala Longhouse

Michael Hirschbichler

Gogodala society is shaped by multiple sets of oppositions which also frame the longhouse’s bipolar construction.

SOCIAL AND MYTHOLOGICAL DUALISM

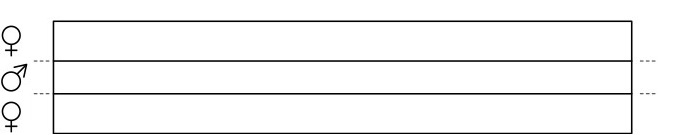

As is often the case in Melanesian cultures, the social system of the Gogodala is based on a division into moieties, called Segala and Paiya, representing a dualistic principle that not only relates to the social dimension but also expands to the enfolding cosmic realm. On the ground, the two moieties are approximately the same size and invariably represented in every genamo. They form exocamic units, in other words, it is forbidden to marry within one’s own moiety. This means a community always consists of two separate but interrelated sections. This social duality is explained in myths that tell of the independent emergence of the two moieties. According to one myth, the Segala are the offspring of an ancestor who fathered the first humans by inseminating a cavity in the ground. Subsequently they travelled to the heavens where they became the sun and the stars. The ancestors of the Payia clan, in turn, were the offspring of a giant snake. They retreated to the ground where they turned into stones.2 Thus we see that the cosmic polarity of earth and sky is founded in myth, giving shape to the sphere of humans who are linked to both entities through the mythological transformation of their respective ancestors. The dualistic principle underpinning social organization is carried over into the body of mythological knowledge in the sense that both moieties have their corpuses of myths, which they carefully safeguard, especially from one another.

The dual social structure is mirrored in the bipolar construction of the longhouse with its two sides, genagoba, separated by a central hall referred to as komo. Although today the two moieties are no longer assigned to either one or the other genagoba, we may assume that this was the case in earlier days. In the nearby Purari district3 one still finds this identification between a moiety and a specific half of a ceremonial house. Moreover, in Gogodala mythology one hears that the two moieties originally inhabited two separate halves of a huge, primeval house made of stone,4 which suggests that, historically, residence too was governed by the same dualistic principle.

GENDER SEGREGATION

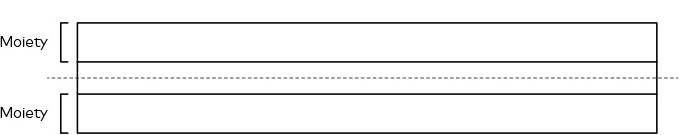

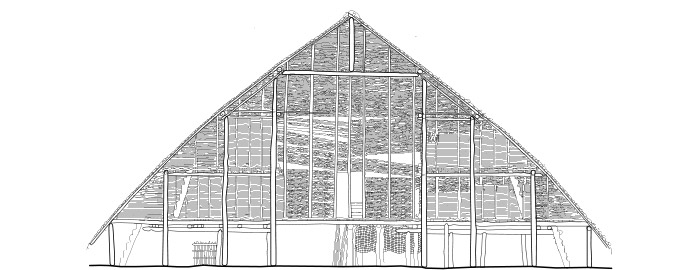

The division of Gogodala society into moieties is complemented by gender segregation, which, not least, finds expression in the spatial polarity of the longhouse and the segregated residential arrangement within the building. Stretching along the entire length of the house and reaching to the top of the roof runs a central, undivided hall called komo.

This is the area where the men dwell and sleep. The actual sleeping places are situated high up under the roof, on platforms referred to as gawaga. Flanking both sides of the komo and separated by walls are the women’s and children’s dwelling and sleeping spaces, genagoba, stretching across two floors. The rooms below are above all used during the day, while the rooms on the top floor, sikiri, is where the women and children sleep at night. In addition, the genagoba are partitioned into separate units with the aid of screens. Some are small serving a single family, others provide space for several families. The genagoba are accessed by side entrances, with stairs leading from the ground floor, whereas the komo is entered by way of centrally arranged stairs, wakali, located at each end of the house. The actual entrances, ogosa, are very small apertures, making the men having to stoop when entering. Thus, all in all, the men’s hall is a very closed space.

While the men are allowed to freely roam the family rooms, women and children are strictly forbidden to enter the komo. The restriction also relates to the central ground-floor space under the actual komo.

Women and children usually avoid this area, which is not specially marked off, while the spaces at the sides of the house, under the genagoba, are the areas where they spend much of their time during the day. Thus, the longhouse is segregated by gender both vertically and horizontally. Gender opposition defines the building’s basic structure and the spatial disposition of everyday life.

OPPOSITION BETWEEN THE SACRED AND THE PROFANE

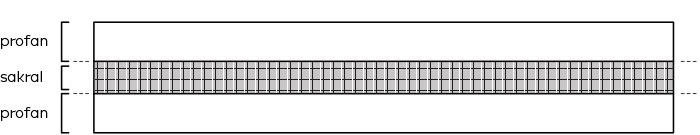

The distinction between male and female areas goes hand in hand with a division between sacred and profane spaces, with the male sphere representing the sacred and the female sphere marking the profane. The komo is not only the men’s habitual abode it also represents the secret sacred space of ritual activity.

Accordingly the walls, or screens, between the komo and the genagoba act as hallowed boundaries separating the sacred centre from the profane periphery. During ceremonies, for example in the context of initiations, the komo becomes the sacred interior while the rest of the building – and the world beyond – become the outside, the profane exterior. Thus the distinction between sacred and profane also creates a ritually effective opposition between inside and outside. Trespassing the sacred boundary during certain rituals could be punished by death.

Apart from the general distinction between the men’s central space and the house’s peripheral spaces, the komo itself is divided into spheres of different grades of sacredness based on the opposition between front and rear. Gogodala longhouses are usually aligned along an east-west axis, with the front of the house, ganipala, facing east and the rear, wanipala, facing west. In structural terms no differentiation is made with regard to front and rear, other than in the ritual context. The majority of important ritual actions are performed at the front end of the komo; this is also where the important senior men reside. The rear end is reserved for the novices, especially upon entering the komo for the first time through the back entrance after several months of seclusion and before being initiated into the first grade.5 The front-back division is also upheld at the end of the initiation to the second grade when ritual dances following a clear choreography are staged at the back of the komo while the senior men play the secret sacred instruments in a secluded area at the front end.

Apart from this overall polarity between a sacred centre and profane peripheral spaces and the distinction between more and lesser sacred areas within the komo, sacredness is also subject to a temporal dimension, in other words, we have fluctuating degrees, a waxing and waning, of sacredness depending on the specific stages of the ritual cycle.

During the preparations for a new initiation cycle and then again prior to the initiation to the final grade, the community undergoes a temporary spatial reorganization in the sense that women, children and non-initiated youths move out of the longhouse and go to live in temporary huts near the gardens. Only the initiated senior men remain in the genamo. During this period, the sacred sphere is extended to encompass the entire building, including the otherwise profane family spaces. At the end of the initiation to the second grade, the women are, by way of exception, granted access to the rear end of the komo. In this liminal ritual phase, the taboo applies only to the area at the front of the komo.

The dual social structure, the gender segregation, the opposition between the sacred and the profane – and the concomitant dichotomy between inside and outside, between the east as the sphere of creation and the west as the realm of death, between the self and the other, etc. – are fundamental features of Gogodala culture and society. Basic differences are expressed as juxtapositions, thus underpinning the bipolarity of the cultural order. Based on the conception that the coeval presence of complementary parts serves as a prerequisite for a harmonious whole, the oppositions verge towards unity. Mutual interdependence and pervasion resolve the inherent cultural, social and religious tensions.

INTEGRATION AND SPATIAL ORDER

The arrangement of architectural space corroborates the concurrence of opposition and integration. The structure of the social and mythological realm, gender segregation as well as the order of sacred space is aligned with the design of architectural space. Bringing the conceptually bipolar spaces together in one building paves the way for integration as regards content. While the principle of duality is widespread in cultures in Papua New Guinea, the Gogodalo genamo is one of the very few cases in which oppositions coalesce within a single construction.6

RITUAL INTEGRATION

The structure of spatial organization and the links contained therein are regularly validated in and through ritual, with the duality of the moieties being lent expression by the choreography of the ceremonies enacted during certain stages of the initiation cycle. Members of both moieties go through the ritual process jointly and at times act on each other, thus confirming each other’s essential quality as parts of a single whole. The same goes for the duality of gender. A key event in the initiation process refers to the ceremonial unification of male and female during the gi maiyata stage performed in the sacred space of the komo, when spatial segregation, otherwise a central feature of Gogodala society, is temporarily suspended by the ritual enactment. At the same time, the ceremonial liminarity engenders a shift in the sacred and profane spheres in the sense that the sacred space is expanded to include those (women and children) who are, under normal circumstances, excluded from it, leading to a temporary absorption of the profane in the sacred. This transient suspension of opposition validates the general principle of duality that otherwise governs lived reality.

Beyond its function of providing a protective space for a specific community, the Gogodala longhouse represents the physical manifestation of fundamental social and religious oppositions. Its bipolar structure creates a dynamic interface in which social, cultural and religious life in all their facets are reflected and dynamized. The vectors of cultural life permeate the architectural space, or, to put it in another way, the spatial structure echoes, channels and transmits all manifestations of social and cultural life. An architecture which includes all social groups, provides space for everyday life and ritual enactments, incorporates the sacred and the profane and merges the present with the mythological past, as the genamo does, can well and truly be called a total architecture.

On the one hand, the totality grows from the identification of the community with a building that defines the universe of living, amalgamating settlement with construction and social organization with architectural structure. On the other, such a totality is not a given, it must be continually constructed by reconciling the differences that characterize all community life in an integral spatial-cultural structure. The total architecture represents the clearly defined and ordered social, religious and cultural – the human – realm that stands apart from the wild natural world, a static and stable sphere in a fluid expanse of constantly changing nature. In the Gogodala landscape of swamps and lagoons with its varying seasons, changing water levels, and emerging and vanishing islands of land, the longhouses built on elevations stand as landmarks, beacons of cultural stability and durability to offset the fluidity of nature. At the same time the bipolar format of Gogodala culture and society represents an approximation to nature. The opposition between the genders, the mythological emergence of an anthropomorphic order from the infinite time and expanse of the surrounding territory and the identification of sacred sites in the natural environment stand for the human attempt to be part of the natural world. The polarities embody the logic interlinking of the cultural and the natural orders. By bringing together the social-cultural and the cosmological oppositions and blending them in the structure of architectural space, nature and culture become aligned. Ultimately, the aim of the total architecture is to transcend the sphere of cultural construction and create oneness between the humans and the world.

Beaver, W. N. 1914. A Description of the Girara District, Western Papua. In: The Geographical Journal (43) 4: 407-413.

Crawford, Anthony Leonard 1981. Aida. Life and ceremony of the Gogodala. Bathurst, Australia: The National Cultural Council of Papua New Guinea.

Williams, Francis Edgar 1924. The Natives of the Purari Delta. Anthropology Reports No. 5. Port Moresby: Government Printer.

Wirz, Paul 1934. Die Gemeinde der Gogodara. Nova Guinea. Résultats des expéditions scientifiques à la Nouvelle Guinée; publ. sous la dir. de L. F. de Beaufort. Bd. 16. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

Isago-Langhaus exterior view and Komo: Architectural Heritage Centre of Papua New Guinea, Papua New Guinea University of Technology, Lae, Papua New Guinea

Short movies

Curators in dialog with objects (in German only, with an English summary)

Trailers

Specials